The European Commission today published a review of the Toy Safety Directive. Toy Industries of Europe (TIE) sees the revision as a big opportunity but also a challenge to ensure that toys remain safe while still being fun for children and affordable for their families.

The current EU Toy Safety Directive (TSD), a safety bible for reputable toymakers, has been instrumental in guaranteeing a diverse range of safe toys for kids throughout Europe. Toys from toymakers who comply with the current Directive are absolutely safe today. It is good to see the strengthening of the free movement of toys within the Single Market by transforming the Directive into a Regulation.

But as the proposal makes its way through its legislative journey, there are several improvements that should be made so that it targets genuine safety risks. We are not convinced the proposal has really hit the nail on the head here. The current text misses the opportunity to tackle the tsunami of unsafe products that non-EU traders sell on online platforms. Neither the Digital Services Act nor the General Product Safety Regulation has provided a solution here. This can only be meaningfully resolved by giving online platforms an importer responsibility when no-one else in the EU is responsible for the safety of the toy.

The new Toy Safety Regulation must not end up banning safe toys or making it too cumbersome or expensive to put them on the market. The new chemical requirements may do just that. In this case, the new rules will be a great gift to those traders who have no intention of complying with it and will continue to sell unsafe toys. This is why the work needs to focus on real science-based safety risks.

TIE also cautions against imposing restrictions solely on toys. “Toys are already stricter regulated in terms of the substances they contain than other products that children are more regularly in touch with” says Catherine Van Reeth, Director-General of TIE. “If toy materials need to comply with much stricter criteria than those other everyday products, our industry – which is 99% SMEs – will struggle to find suppliers ready to provide us with such specific, niche materials at a reasonable price.”

Any new rules put forward in the revised TSR can only be effective if they are enforceable. This will require more than a Digital Product Passport. If toys can be copied, so can product passports. Real enforceability requires an increase in resources for market surveillance and other agencies that help to implement the rules. If not, rogue traders will continue to ignore the rules, as they do today, and because they have lower compliance costs, they can sell at a cheaper price. Consumers then unknowingly buy dangerous toys.

TIE will engage with policy makers throughout the legislative process to ensure that the new rules ensure children’s safety while sustaining the joy, creativity and affordability of toys.

Q&A on the Toy Safety Directive revision

The current Toy Safety Directive came into force in 2009. It is the main body of rules that determine what makes a safe toy. Besides the Toy Safety Directive, toy manufacturers also need to ensure their products comply with several other applicable pieces of EU legislation such as REACH, RoHs for electronic toys, the Radio Equipment Directive etc.

The original Directive dated from 1988 and was updated in 2009. Such updates keep the rules adapted to new toy trends and new developments in scientific knowledge. However, seeing as the core obligation on toy manufacturers in the current Directive is that they need to ensure they only market safe toys, there should never be a safety void. The current update is in a large part motivated by the Commission’s Chemical Sustainability Strategy.

Toys that are compliant with the TSD are already safe. What the revision mostly will do is to make compliance and enforcement easier or more complicated.

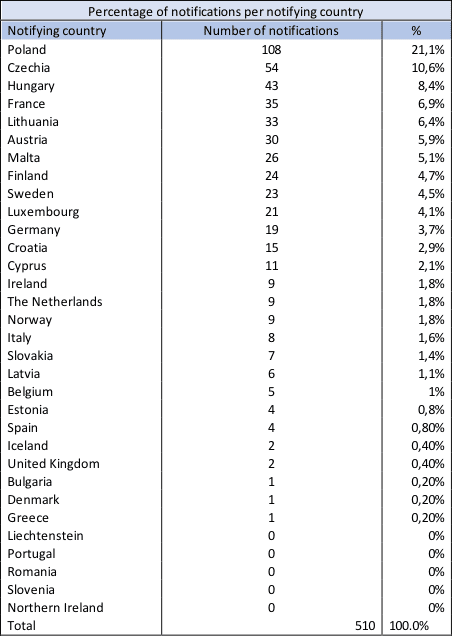

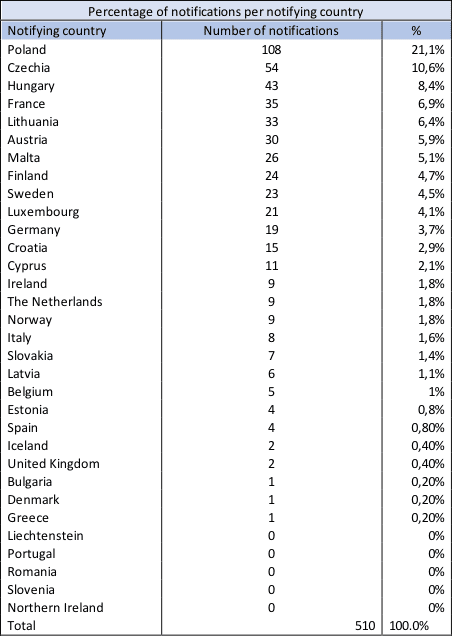

Unsafe toys continue to reach the hands of children in Europe, despite the already strict legislation. The simple reason: many rogue traders do not care about safety and do not care about following the rules. In this case, new rules will not help. Improving the enforcement of existing rules will. We need a harmonized maximum enforcement approach. Currently there are marked differences in how effective market surveillance is in the EU. For instance, the below data for 2022 clearly show that only a small number of Member States notified the majority of unsafe products on the EU Safety Gate. This is the same every year!

When countries report no or only a few dangerous toys, it either means that no enforcement actions take place or it could mean that the actions that do take place are largely unsuccessful. This is possible when the enforcement action is targeted at reputable toymakers and retailers. Then the ‘catch’ is bound to be disappointing but it does not provide a good picture of the presence of unsafe toys as we know they are out there.

(source: European Commission’s Safety gate website)

No, there is no way market surveillance can catch all of the unsafe toys and definitely not when they are reaching the consumer direct from a non-EU country in a single parcel rather than when they arrive in bulk in containers in the EU. There are also simply too many of them, especially online. This is why we also need to look at prevention. An avalanche of unsafe toys reaches the European consumer through the services of online marketplaces. Thanks to the Digital Services Act, they need to know their business customer but this is not enough. Where there is no EU manufacturer or importer and where they have not assessed who the relevant EU economic operator is, the online marketplace should have an importer’s obligation and be one of the ‘economic operators’ defined in the TSD.

No. They are a good start, but do not fully address the issue for toys which have much more detailed safety requirements than other products. In particular when a seller is based outside the EU and nobody takes responsibility for it. Currently there is no guarantee somebody in the EU will take responsibility for the safety of the toy, nor that somebody can be held liable.

The DPP is suggested by the European Commission as a carrier of information. This can be all kinds of information that would for instance be available through a QR Code. For some information, it provides certain opportunities for toys as their often-small packaging is already quite crowded with all the traceability information and safety guidance. Recently, we have also had to start adding sorting information for the packaging and the toy that differs from country to country. It would be beneficial and less confusing for the consumer if we could move that information from the package to the digital carrier so consumers from different countries could be guided towards ‘their’ information.

In a very limited way, maybe. The DPP, in providing systematic access to the Declaration of Conformity, can help to check documents but it does not help testing for safety. All documents can be faked, also those accessible through the DPP.

Implementing a DPP will need a lot of effort from SMEs and from the toy sector as a whole as our companies have a huge number of SKUs that keep changing all the time. In any case, the process for applying a DPP should be as simple as possible! It is doubtful at the moment that – in terms of safety – the benefits weigh up to the costs.

CMR stands for carcinogenic, mutagenic and toxic for reproduction, meaning CMRs can cause cancer, change your genetic make-up or influence reproductivity. CMRs may be present in toys as byproducts of chemical processes or in very low trace levels through contamination but they may also naturally occur in some materials: think of formaldehyde in natural wood. The simple presence of these CMRs does not automatically mean children are at risk from them.

The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs that produce, store, and secrete hormones. When functioning normally, the endocrine system works with other systems to regulate the body's healthy development and function throughout life.

Endocrine disruptors are substances in the environment (air, soil, or water supply), food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that interfere with the normal function of the body’s endocrine system. Since EDs come from many different sources, people are exposed in several ways, including the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the water we drink. EDs also can enter the body through the skin. (source: Endocrine Society)

Well known EDs are certain phthalates (used by non-scrupulous traders to make soft PVC). These have effectively been banned in toys for more than 20 years.

The EU is currently deciding which substances should go on a list of identified EDs.

No. Toys that are compliant with the Toy Safety Directive will not pose a risk to children. The Commission’s own evaluation of the Toy Safety Directive also provides no evidence of concrete problems that compromise the health and safety of children. No examples of (chemical) safety concerns with compliant toys are mentioned/known.

No CMRs or EDs may be present in a quantity that could present a health risk to children. This rule is specific to toys, other products such as clothing, bedlinen, furniture, video games consoles etc have no such safeguard. In most cases, children will also not be exposed to them – should they be present. For instance, printed circuit boards in electronic toys may contain these substances, but due to their inaccessibility, children will never be exposed to them. Some plastic materials may also contain residues of chemicals used to produce them, but for instance, in the case of ABS, it has been demonstrated that they do not migrate out of the material, resulting in safe use. Toy Industries of Europe has never seen any evidence of toys that are compliant with the Toy Safety Directive posing a risk to children's health.

We are not sure. We have repeatedly asked the Commission to see the evidence on which they base this statement but have never received any convincing evidence that toys that comply with the Directive pose a problem in terms of CMRs.

A more rational and effective approach to setting limit values for chemicals can address any specific concerns on exposure to CMRs while not banning toys that are safe. This approach needs to be scientifically sound, result in a real difference in terms of safety and not ‘single out’ the small toy sector to meet stricter requirements than other sectors (unless there is a demonstrated safety risk). If concerns that are non-toy-specific need to be addressed, this should be done through more general legislation such as REACH. This will make alternative substances a lot more accessible and affordable. Suppliers will not adapt themselves easily to a ‘niche’ requirement for a tiny sector. Also, from a child protection point of view, this approach makes more sense.

It is true that toys top the list of EU Safety Gate almost every year. TIE monitors these results carefully and every year around 98% of those unsafe notified toys originate from toy manufacturers who have no intention to follow the rules. This has nothing to do with reputable toy manufacturers but with rogue traders who want to make a quick profit without caring for the children’s safety. Restricting the rules will not help one iota here.

We are afraid that some of the proposals will in fact have the opposite effect:

- Requirements that are not based on sound scientific and safety-focussed evidence risk banning toys that are in effect safe. To avoid this, exemptions would need to be worked out by Scientific Committees but it is doubtful whether they will have adequate resources for this and what kind of delay this will bring;

- Requirements that are not based on sound scientific and safety-focussed evidence risk boosting the sales of sales of unsafe toys from traders who do not care about the rules. They will not need to raise their prices whereas reputable manufacturers, due to complicated approval processes, the need for unnecessary alternative substances or materials, changes in production processes, more testing costs, etc. will need to raise prices. This would be a great gift to rogue traders, while possibly endangering the continued success of some of the reputable SMEs who make up the majority of the industry.

- There will be less enforcement as market surveillance authorities may not be able to afford to test the toys they want to check for compliance. Just one test can cost €10,000. National authorities will need a very large budget if they want to do any meaningful checks against requirements that are disproportionately difficult to meet.